Solana Beach caregiver Steve Whitecotton started his Wednesday as he always does, by writing the day’s schedule for his wife on a small whiteboard in the living room of their one-bedroom apartment.

9 :30 a.m. Lauren from UT visiting

11 a.m. Lunch out!!!

12:30 p.m. Steve cycling. Back by 2 p.m.

4 p.m. Roasted chicken

Throughout the day, it’s displayed prominently in front of the couch, and he erases each line as it’s completed. Writing out a schedule helps Steve, 66, ease feelings of anxiety for his wife Marilynn, 82, who was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease seven years ago.

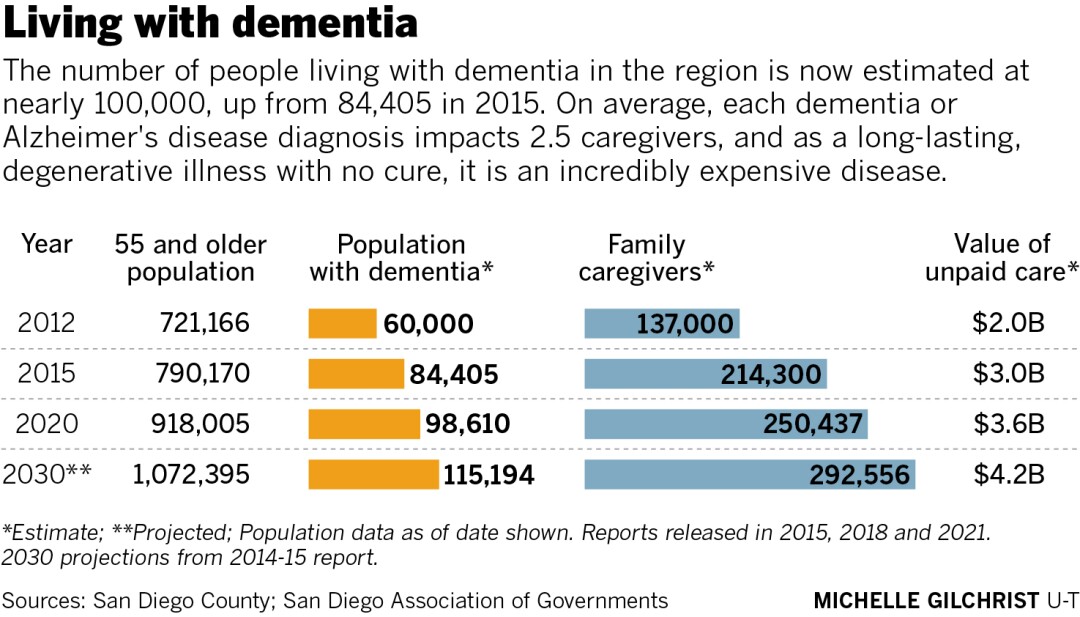

Marilynn is one of nearly 98,610 seniors living with dementia in the region, according to the latest report from The Alzheimer’s Project, a county health initiative. That’s a nearly 17 percent increase from the 84,405 reported in 2015.

What’s more, it exceeds the original estimate of 94,000 diagnoses officials predicted the county would reach nearly 10 years from now. New estimates say the number of people with dementia in the region is expected to rise to 115,194 in 2030, according to the report published this spring.

It’s a moving target that will require a mad dash from local health care systems to keep up with the demand for services.

What’s driving the increased projections? County officials say a number of factors account for the rise, including adding other forms of dementia to the calculation and a significant push from the county, geriatric physicians and nonprofits to educate the public about dementia while pushing for earlier diagnosis.

The increase also reflects better reporting and earlier diagnosis of dementia, officials say. But a large number of residents are still being undercounted.

As the number of San Diegans 55 and older continues to grow, the population of people living with the disease is expected to increase accordingly.

"(The increase) wasn’t really a surprise, we know that there are so many people who still go undiagnosed,” said Eugenia Welch, Alzheimer’s San Diego president and CEO. “Still, I think there’s probably a large population of people out there who are not counted in that number because they haven’t been properly diagnosed yet.”

Over time, there will also be a rising burden on the local health care system and families who provide hours of unpaid care for their loved ones.

Expensive and exhausting

Steve Whitecotton writes a daily agenda on a whiteboard for his wife Marilynn who was diagnosed with dementia in 2014.

(Jarrod Valliere / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

Alzheimer’s disease is the third-leading cause of death in San Diego County, according to the county report, compared to the sixth-leading cause of death nationwide.

As a long-lasting, degenerative disease with no cure, Alzheimer’s disease is an incredibly expensive disease to care for over the course of its progression.

A diagnosis of dementia impacts someone’s friends, family, the local health care system and the region as a whole.

Is the county prepared to meet the demands of this growing population? Yes, in some ways. But others believe the region remains ill-equipped and health care providers, political leaders, public health officials and advocates are scrambling to fill some serious gaps.

The race to keep up with the needs of this demographic is reflected across the country.

The Alzheimer’s Association reported this year there are now 6.2 million Americans age 65 and older living with the disease, and that number is projected to more than double by 2050. In California alone, there are about 690,000 who have Alzheimer’s, with a projected 21.7 percent increase within the next four years.

Those figures just show the prevalence of the disease, not actual numbers, as many people do not receive a proper diagnosis, said Katie Croskrey, executive director for the Alzheimer’s Association San Diego/Imperial chapter.

Patients sometimes don’t always share everything with their physicians, who in turn don’t always ask about or evaluate patients for memory loss.

“As somebody gets older and they start to have some problems with their memory, it’s a frightening thing,” Croskrey said. “Sometimes people that are having problems with their memory, they don’t bring it up with their doctor.”

One of the goals of the county’s Alzheimer’s Project Clinical Roundtable is to educate local primary care physicians in a push for earlier diagnosis.

In doing so, they may be able to access treatments that can delay the progression of symptoms that aren’t as effective late in someone’s prognosis, said Kristen Smith, Aging and Independent Services health and community operations chief.

Families can also set up systems early on to make later stages of caregiving easier, like meal delivery services, estate planning, long-term care planning and more.

“Very importantly, early diagnosis provides that time to do life planning and get service supports in place,” Smith said.

Impact of dementia on caregivers

Steve Whitecotton uses software developed for dementia and Alzheimer’s caregivers to help care for his wife and share health updates with their family, who could be tapped to help provide care for Marilynn should something happen to him.

(Jarrod Valliere / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

As dementia progresses, and its symptoms of confusion and anxiety increase, it not only takes a toll on the person diagnosed with the disease, it also impacts the family members, romantic partners and friends who care for them.

Caregivers, like Steve, experiment to find ways to help their loved ones through all the ups and downs. Glancing at the whiteboard reminds Marilynn of where her husband is during his bike ride, and what’s happening next, so she asks him less frequently and Steve’s stress is more manageable.

“It works out really well, and he’s great about organizing it enough so I get it,” Marilynn said.

In the months before her diagnosis, Marilynn would get lost driving to meet her husband for lunch at his office.

“I thought it was a little odd, but she’d realize she was at the wrong building and come to the correct building and pick me up, so I didn’t think much about it,” Steve said.

In January 2014, when she called her local doctor’s office asking for directions, Marilynn repeated them back as if she was driving in Los Angeles. She was then evaluated for dementia, giving up her driver’s license in the process before she might forget the meaning behind traffic signals.

After months of evaluation and tests, she was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s that March. In an interview Wednesday, June 2, Marilynn complimented her husband for how he’s cared for her through her worsening symptoms.

“He was very patient, and that really made a difference,” she said.

Still, the stress of repeated questions and increasing levels of care do impact Steve, so he uses daily physical activities such as walks and bike rides to maintain his mental health.

Because the cost of professional caregiving for a long-term health condition like dementia can be prohibitive, much of the burden of care falls on those within the person’s family.

County health officials report there are approximately 250,437 people acting as caregivers for their loved ones, providing $3.6 billion worth of unpaid labor.

As a result, caregivers often put in endless hours of care for their loved one, neglecting their own health care needs. The cost of treating the physical and emotional impact caregiving has on family and friends is approximately $182.6 million, county officials report.

There’s also a financial impact on caregivers, both because of the high cost of health care for dementia and because providing care at home may mean caregivers give up full-time employment.

An AARP survey early last year before the novel coronavirus pandemic started found that about 61 percent of unpaid, family caregivers work a full- or part-time job.

Others, however, reported having to scale back or quit their jobs because the cost of hiring a professional caregiver is too steep. Some lost job benefits, retired early or turned down promotions to focus on caring for loved ones.

In the Whitecottons’ experience, Marilynn had already retired from her job as a travel agent when she was diagnosed. Steve, however, retired from his IT job a year or two earlier than planned to be home with her full time.

“I was concerned about her and I just wanted to be around to see what was going on,” Steve said.

After getting the dementia diagnosis, it was also too late for Marilynn to qualify for long-term care insurance. And at first, her insurance didn’t cover the cost of a Galantamine prescription — a cognition-enhancing drug that slows the progression of symptoms — costing them $100 per month out of pocket.

Is San Diego prepared? Kind of.

Steve and Marilynn Whitecotton at their home in Solana Beach.

(Jarrod Valliere / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

Advocates at local nonprofits supporting seniors and their caregivers say San Diego is better prepared for an increasingly aging population and greater number of dementia diagnoses than many other counties across the country.

Organizations such as the Southern Caregivers Resource Center and the San Diego Caregiver Coalition address the needs of caregiving as a whole, while the Alzheimer’s Association San Diego chapter and Alzheimer’s San Diego focus specifically on dementia care.

Through these and other nonprofits in the region, there are educational opportunities for people with dementia and caregivers to learn about the disease, as well as support groups where they can relieve stress and learn from their peers.

In addition to the Clinical Roundtable, the county’s Alzheimer’s Project has the Collaboration4Cure branch bringing in medical research funding into the county.

In-home respite care is also available through the county’s voucher program, which launched as a $1 million effort in 2019, spearheaded by former Supervisor Dianne Jacob.

The initiative aims to prevent burnout by supporting middle-income caregivers who neither qualify for low-income respite programs nor can afford to hire a care provider.

San Diego also has private and nonprofit adult day care programs, which provide respite for full-time, unpaid caregivers or allow them to maintain a job while keeping their loved one at home.

Where San Diego has room for improvement

But as prepared as the region is in many ways, San Diego isn’t unique in that there remain shortfalls to addressing the needs of caregivers and dementia patients.

“We know that Alzheimer’s is one of the most expensive illnesses a family can encounter or a person can encounter; it’s the largest strain on the Medicare system,” Welch said. “If we can get more support services in place early on to help families and to help the people that are diagnosed with dementia, it’s only going to be a benefit to our community as a whole.”

More long-term care facilities are already needed to meet the needs of today’s seniors, as well as neurologists, psychiatrists, professional caregivers and other geriatric health care specialists, Dr. Steve Koh said. He chairs The Alzheimer’s Project education committee for the Clinical Roundtable and is an associate professor in the Psychiatry Department at UC San Diego.

“It’s an evolving disease that has a lifespan of anywhere from three to 20 years,” Koh said. “During that stretch of time, these patients could become behaviorally out of control, really medically ill, depressed and just become unstable on their medicines.”

In San Diego, there’s currently a capacity of 8,805 beds in skilled nursing facilities and 20,465 in residential care facilities for the elderly, which include nursing homes dedicated to memory care.

Memory care facilities often have waitlists, so the rate of new facilities being built already needs to increase to meet the demands of today’s dementia patients.

“We just don’t have enough of those, and that’s concerning because the population is aging. It’s highly problematic,” Koh said.

Another area where Koh sees room for improvement comes to expanding the local population of health care providers from diverse backgrounds, in particular those who are Hispanic, Black, Filipino and Asian.

An Alzheimer’s Association survey this year found that discrimination is a barrier when it comes to accessing dementia health care for people of color.

The majority of Black respondents — 66 percent — said their racial identity hinders their access to excellent Alzheimer’s disease care, as did 40 percent of Indigenous people, 39 percent of Hispanic Americans and 34 percent of Asian Americans .

On the caregiver front, half or more of respondents identifying as non-White said they’d experienced discrimination within the health care system when advocating for their care recipient.

“The families and patients do well with those they identify with, and we don’t have that level of diversity,” Koh said.

FDA may soon approve new Alzheimer’s treatment

Something that could alter the landscape of dementia care is an effective drug that slows the progression of the disease, or eventually cures it.

Treatment won’t just improve outcomes for people who are currently diagnosed, but it could inspire more people to seek a diagnosis, said Dr. Michael Lobatz. He’s a neurologist with Scripps Health who serves as co-director for the Clinical Roundtable on the county’s Alzheimer’s Project.

Treatment, in Lobatz’s words, “might be right around the corner,” and early diagnosis would increase the chance that treatment can effectively delay severe symptoms

“The desire to be screened and evaluated will go up on all levels,” Lobatz said. “Physicians will want to do it, patients will want to do it. This will be a big, major sea change at that point.”

On Monday, June 7, the FDA will vote whether to approve Aducanumab, a monoclonal antibody from the neuroscience-centered biotech company Biogen. It’s designed to bind to and remove amyloid beta plaques from the brain to slow neurodegeneration and disease progression.

If approved, Lobatz said, it would be the first time in 18 years that a drug to change the clinical course of Alzheimer’s disease has entered the market.

But through the course of its development and testing, there has been some controversy around the efficacy of Aducanumab, Lobatz said.

The monthly, intravenous infusion is also expected to be expensive. Estimated to cost up to $50,000 per year, it would also require a pricey PET scan to confirm amyloid beta proteins are present in someone’s brain before they can begin treatment.

For detailed information on getting started with caregiving, and a map of nonprofit organizations throughout the county, visit CaregiverSD.com.

— Lauren J. Mapp is a reporter for The San Diego Union-Tribune

"with" - Google News

June 07, 2021 at 02:25AM

https://ift.tt/3fWNYpl

Is county ready to meet demands of growing number of residents with dementia? - Del Mar Times

"with" - Google News

https://ift.tt/3d5QSDO

https://ift.tt/2ycZSIP

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Is county ready to meet demands of growing number of residents with dementia? - Del Mar Times"

Post a Comment